This story was originally published by Canary Media and is reproduced here with permission.

Starting as soon as next year, the electric bills of a majority of Californians could be based not just on how much power they use, but also on how much money they make. That would be a nationwide first — and depending on who you ask, it could be the fairest and best way to help people adopt clean electric vehicles and heating, or an unjust and unworkable scheme that could discourage rooftop solar and energy efficiency.

An energy law passed last year in California requires state utility regulators to come up with a plan for charging customers income-based fixed fees as part of their electric bills by July 2024. The California Public Utilities Commission set last month as the deadline for interest groups to file proposals for how to create these “income-graduated fixed charges” for the 11 million customers of the state’s three big investor-owned utilities, Pacific Gas & Electric, San Diego Gas & Electric and Southern California Edison.

Based on the public feedback submitted to the CPUC by everyday customers, it’s a wildly unpopular idea. Looking into customers’ income tax records to charge them monthly fees they can’t avoid, no matter how frugal they are with electricity use or how much they invest in rooftop solar and batteries, could trigger a political backlash from customers already fed up with rates that have been rising at three times the rate of inflation and are expected to keep rising in future years.

But supporters of income-graduated fixed rates argue they’re not just a fairer way to shift the burden of paying for utility costs from lower-income customers to those better able to afford it. They’re also a way to encourage people to switch to electric heating and cooking and swap out their gasoline-powered cars for electric ones. (Opponents disagree with that claim; more on that to come.)

The rationale for income-based fixed charges

Here’s an important fact underlying this debate: The adoption of income-based fixed fees would not increase or reduce the total amount of money that California’s big three utilities collect from their customers. Rather, the new fixed fees would lead to some customers paying more than they do today and some paying less.

In the U.S., utilities charge their customers for how many kilowatt-hours of electricity they consume — so-called volumetric charges — and in most cases also charge them fixed fees to cover fixed costs of maintaining the grid and broader electrical system. The fixed costs — which include maintenance and expansion of distribution and transmission grids, energy-efficiency programs, low-income bill-assistance programs, and more — account for roughly half of the costs paid by customers in California.

Those costs are growing far faster than the cost of actually generating electricity, however. One of the biggest such costs in California is the billions of dollars being spent on hardening and burying power lines to reduce the risk of them sparking wildfires. Utilities are also bearing the costs of compensating the victims of wildfires caused by poorly maintained grid equipment, like the devastating 2018 Camp fire sparked by a failed PG&E power line, which ultimately drove the utility into bankruptcy protection.

Currently, the three big utilities in California have very low monthly fixed charges compared to national averages. The costs of grid maintenance and the like are incorporated into per-kilowatt-hour volumetric charges, which means those charges are high. The higher the per-kilowatt-hour prices that people have to pay for increased electricity use, the less affordable home electrification will be, fixed-charge advocates argue — and the more lower-income and disadvantaged communities may be harmed by it.

The idea of charging customers based on their annual incomes has moved from an academic proposal to an official California policy with surprising speed. It was first unveiled in 2021 by researchers at the Energy Institute at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. It’s unclear which state legislator added it to last year’s energy bill, AB 205. The provision was largely overshadowed by the bill’s other contentious components, such as halting the planned closure of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant and spending billions of dollars to bolster the grid against electricity shortfalls.

Meredith Fowlie, faculty director at the Energy Institute, argued in an April blog post that the big three California utilities’ per-kilowatt-hour prices “are too high because we’re effectively taxing grid electricity consumption to pay for costs that don’t vary with usage. […] These too-high electricity prices are slowing progress on electrification and straining the pocketbooks of lower-income households.”

Fowlie noted that her own electricity rates would go up under this proposal. “Although I don’t love the idea of sending more money to PG&E every month, I see this bill increase as a feature, not a bug, of a reform that aims to recover power system costs more efficiently and more equitably,” she wrote.

But there’s a lot of disagreement over whether a novel move to treat utility bills more like income taxes is the best way to address equity concerns and other issues.

Supporters of income-based fixed charges include the big three investor-owned utilities and the Energy Institute at Haas. Environmental groups including the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council have traditionally opposed fixed charges, but they’ve filed fixed-charge proposals, acknowledging that the cost challenges Californians face could justify putting the concept into practice. Opponents include rooftop-solar and efficiency supporters who fear the shift could unfairly punish customers who invest in reducing their electricity usage, as well as anti-tax groups that have decried the proposal as a hidden tax on utility customers. Still, some of these opponents are proposing plans for new fixed charges so as to take part in the decision-making process.

Even among supporters of income-based fixed fees, there’s wide disagreement about how large they should be and which income brackets should pay how much.

Utilities are pushing for high fixed fees

The state’s three big utilities teamed up to submit a proposal to the CPUC, and it’s drawn heavy fire for the sheer scale of the fixed charges it would impose.

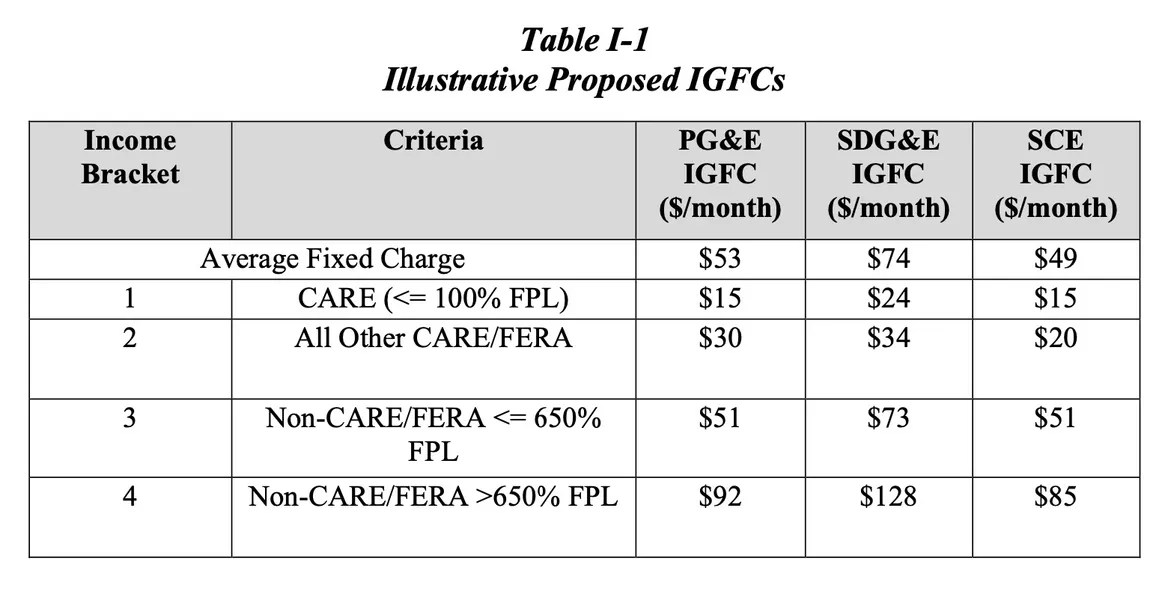

Under the joint utility plan, households with annual incomes between $ 28,000 and $ 69,000 would pay from $ 20 to $ 34 per month in fixed charges. Those earning between $ 69,000 and $ 180,000 would pay $ 51 to $ 73 per month, and those earning more than $ 180,000 would pay $ 85 to $ 128. Currently, the average total household electric bill in California is $ 164 a month.

Low-income customers who currently receive assistance to pay their electric bills would not be exempt. These California Alternate Rates for Energy (CARE) customers — whose annual earnings are at or below the federal poverty level (FPL) — would pay $ 15 to $ 24 per month in fixed fees.

The utilities say these fixed charges would be counterbalanced with much lower per-kilowatt-hour rates on the electricity that customers consume. They forecast that most customers — all but those in the wealthiest bracket — would save money on their electric bills overall, an average of between 4 and 21 percent, or $ 89 to $ 300 per year.

“This proposal aims to help lower bills for those who need it most and improves billing transparency and predictability for all customers,” Marlene Santos, PG&E’s chief customer officer, said in an April statement.

But opponents question these utility figures. Ahmad Faruqui, an energy economist critical of the state’s recent policies on rooftop solar and utility rate design, analyzed the utility proposal and found that many customers who aren’t on CARE rates could face significantly higher bills.

What’s more, those who use the least electricity today would face the steepest cost increases under the utility proposal, he said, while those who use the most would see the largest cost declines.

“This is contrary to 40 years of energy-efficiency policies in California,” he said. “You’re going to hit a lot of customers with a penalty that is really ill-deserved.”

Going with the utility proposals could instantly catapult fixed charges for customers of California’s big three utilities to levels unmatched anywhere else in the country. Analysis by clean energy research firm EQ Research found that the utility plan, if enacted, would result in the nation’s highest monthly fixed fees, well above the current highest, the $ 37.41 monthly fixed charge levied by Mississippi Power, and nearly five to seven times the national average for utility fixed charges.

That, in turn, could lead to significant backlash from customers who aren’t able to take action to reduce their bills, Faruqui said. “Why create this huge rate shock for at least half of these 11 million customers?”

Other groups propose more moderate options

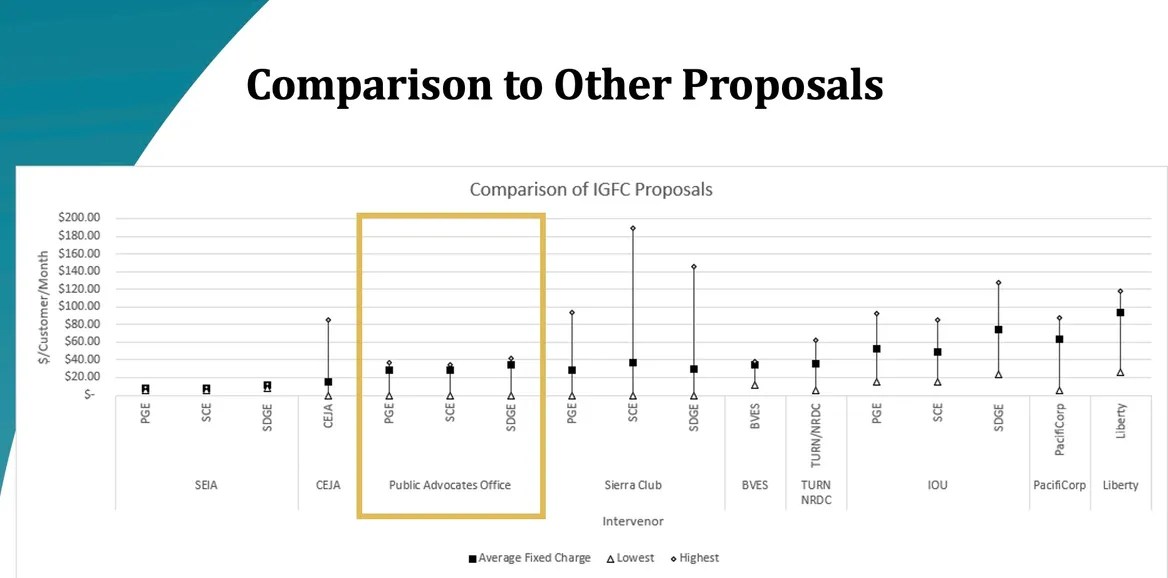

The risk of “rate shock” is top of mind for other groups that have submitted proposals for more modest income-based fixed charges. This chart from the CPUC’s Public Advocates Office, which is tasked with protecting consumers, shows the range of fixed charges that different proposals would assess on customers of varying income levels (the vertical lines on the chart) as well as the average of those fixed charges (the black box on each line).

This chart shows that utilities — the three big ones plus PacifiCorp and Liberty, clustered on the right side of the chart — propose higher average charges than any other groups.

One proposal that would reduce average fixed charges by boosting charges on the highest earners comes from the Sierra Club. Rose Monahan, staff attorney at the environmental group, said the aim is to minimize harm to lower- and middle-income earners.

“Historically, Sierra Club has not been supportive of a fixed charge,” Monahan said. “It discourages energy conservation and efficiency, and if you have a high fixed charge, it can discourage people from investing in rooftop solar or a battery.”

Yet an income-based charge represents “a real opportunity to address historical inequities in energy rates,” she said. And “even with a volumetric rate reduction that will encourage electrification, the rates in California are still so high that people are incentivized to conserve.”

But the Sierra Club’s plan would have fixed charges cover fewer utility costs than the utilities’ proposal, Monahan said. “We have some concern with the cost components that the [investor-owned utilities] are proposing to include in a fixed charge,” Monahan said, including distribution costs, even though they’re connected to how much electricity is being consumed.

Including so many costs in fixed charges could allow utilities to argue for increasing them in their general rate cases, the proceedings that occur every three years in which utilities ask regulators for permission to raise rates or alter rate structures, she said.

Sierra Club’s fixed charges, by contrast, would include “only costs that are actually fixed,” she said, such as utility-administered efficiency programs and connecting new customers to the grid.

The Sierra Club’s plan would balance its reduced costs for lower-income earners by boosting them for higher-income earners, a structure modeled on California’s relatively progressive personal income tax, she said. While that seems fair to the Sierra Club, it does carry certain risks.

“When you get too high a fixed charge for high income, it becomes cost-effective for those folks to put a rooftop solar system on their home and batteries and just disconnect from the grid,” she said. That’s known as “grid defection,” and while it hasn’t become a significant trend yet, the higher utility rates rise, the more likely it may become one.

Tapping alternative funding to keep charges lower

The risk of rate shocks, political backlash and grid defection has guided other proposals that would limit how much the highest-income earners pay.

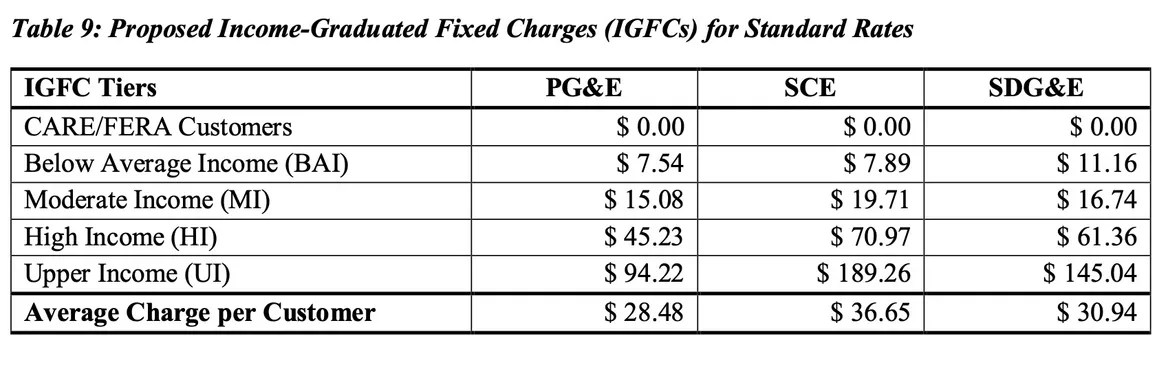

The proposal from CPUC’s Public Advocates Office would both reduce fixed charges for the lowest-income earners to zero and limit how high they can go for the highest-income earners, as this chart indicates.

Matt Baker, director of the Public Advocates Office, highlighted the pressing need for action to reduce the impact of high and rising utility rates for Californians. The state’s average annual electricity costs are 25 percent higher than the national average and have well outpaced the rate of inflation over the past 15 years. Utility costs are set to rise even more dramatically in coming years, which will lead to higher customer rates at the same time that state policy is pushing people to buy EVs and electric heat pumps.

“Twenty years from now, we’re going to be using twice the amount of electricity we use now,” Baker said. “For the first time since the 1980s, we want people to use more electricity.”

Changing rate structures can’t alter the underlying costs that utilities are incurring, said Mike Campbell, a rate-design expert at the Public Advocates Office. “Our group has to work on how to set rates to do that,” and “we cannot look away from the inequities that are being created.”

At the same time, “the commission should move cautiously to not create backlash, to not create unintended consequences,” he said.

That’s why the Public Advocates Office has proposed a method to avoid fixed monthly charges for low-income customers while also limiting fixed monthly charges for the highest-income earners — tapping the California Climate Credit, a program that distributes money collected from the state’s greenhouse gas cap-and-trade program.

Currently, this program gives customers credits on their energy bills twice a year, totaling roughly $ 100 to $ 200 annually for many state residents. The Public Advocates Office would redirect that money to reducing monthly fixed charges, Campbell said.

“To be fair, someone might say, ‘You’re taking some money from some folks to do this,’” he said, since some of the program’s funding would be redirected from higher-income earners to those who earn less. “Yes, that would be happening,” Campbell acknowledged — but it’s a relatively small amount of money, and the benefits of using it to reduce future fixed charges would outweigh the benefits of twice-annual adders to customer bills, he argued.

How can utilities know how much money their customers make?

Hanging over these relatively abstract questions of rate design is a more fundamental problem: How can utilities learn how much money their customers make, information they would need in order to implement income-based fixed charges?

Utilities aren’t legally authorized to access federal or state income-tax data about their customers, Faruqui noted. Nor can they rely on customers volunteering this information, given privacy concerns and the risk of customers misstating their income to receive lower rates.

“This is mired in legal and administrative complications, even before we get to the magnitude of the fixed charge,” Faruqui said. “That’s why nobody else has done it.”

Baker of the Public Advocates Office agreed that this is a tricky question. “We don’t want the utilities to have this information or to be responsible for it,” he said. Still, there are ways to work around these restrictions that can be “seamless for the consumer and as unintrusive as possible,” he said.

Utilities and regulators are already tackling challenges around income verification and customer privacy in order to administer income-qualified rates like CARE and Family Electric Rate Assistance, he said. Those programs rely on customers self-reporting their income, along with follow-up income-verification tests that are less than ideal in terms of administrative cost and complexity, he said.

Over the past few years, the Public Advocates Office has been developing plans for dealing with these problems that could be applied to broader income-based rate structures, Campbell said.

One would be to enlist the California Franchise Tax Board to supply data to the CPUC via an anonymized database, he said. That database would include the vast majority of utility customers who have paid state income taxes in the past year.

But it wouldn’t actually expose any personal income information to the utilities, Campbell said. Instead, “the utility would ping that database and ask, ‘Should this account be in income bracket A, B or C?’” he said. Because no actual personal income data would change hands, this would avoid utilities intruding into customers’ private lives. “It’s fast, it’s secure, and the customer wouldn’t need to do anything.”

The problem with this approach is that it would require California lawmakers to authorize the tax board to share this data with the CPUC. The tax board already shares data in similar ways with other state agencies, so “we’re hopeful that the legislature would work on that, sooner rather than later,” to meet the July 2024 deadline, he said.

In the meantime, the Public Advocates Office is considering working with credit-rating agency Equifax to access its customer income data collected from paycheck-processing providers and other sources, in a similar anonymized manner, he said. That would require a more onerous customer process, however.

The system would assign all customers to the highest income bracket, then require them to contact their utility to attest their actual income. The utility would then inquire with Equifax to determine if the customer’s claim was accurate or not, again with no access to the customer’s actual income.

“The part we don’t like so much is that it requires the customer to do something,” Campbell said. But absent the legislature telling the state tax board to work with the CPUC, “it’s the lightest touch we could come up with.”

Tangled up with rooftop solar and much more

At the heart of the disputes over income-based fixed charges is a challenging dynamic: High per-kilowatt-hour rates might discourage some people from adopting electric heat pumps or cars, perhaps lower-income people in particular. But the same high rates might encourage different people to install rooftop solar and home batteries and make their houses more energy-efficient, perhaps higher-income people especially. So how should those competing interests be balanced?

The conversation about income-based fees is enmeshed in a much larger set of ongoing debates about how California should structure utility rates and policies to foster a shift to clean energy in an equitable way. Opponents of income-based fixed fees say they are simply another layer of unnecessary complexity meant to solve a problem that could better be tackled in other ways.

The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) opposes income-based fixed charges, but given that the law now calls for them, the group has proposed a regime that would keep the charges much lower than any of the other proposals before the CPUC. Tom Beach, principal consultant at Crossborder Energy, argued in testimony on behalf of SEIA that fixed monthly charges aren’t just the wrong way to encourage people to electrify, but the wrong way to align what customers pay for power with the investments needed to reach California’s clean-energy goals.

“Far more important to promoting electrification are cost-based, time-sensitive volumetric rates,” Beach said. Customers of California’s big three utilities already pay time-of-use rates that charge different per-kilowatt-hour prices based on the hour that electricity is being consumed, he noted.

Time-varying rates are an important way to encourage customers to use less power when it’s most expensive to provide — such as during hot summer evenings when electricity demand risks outstripping supply — and to use more power when electricity is cheap and abundant, such as overnight when demand is lower, or at midday when solar power is flooding the grid.

Because many of the costs of running a utility are tied to building a grid that’s sized to meet peak demand, time-varying rates that encourage customers to reduce those peak demands can have a long-term impact on those grid costs.

Unfortunately, the issue of time-based rates versus fixed monthly charges has been tangled up with California’s fractious conflicts over rooftop solar policy. SEIA and other pro-rooftop-solar groups have been the loudest opponents of fixed monthly charges to date. And many of the groups that have fought for years to cut the value of rooftop solar are now advocating for the income-based rate structure, such as the Energy Institute at Haas, the Natural Resources Defense Council and The Utility Reform Network, a ratepayer advocacy nonprofit.

The CPUC’s recent changes to net metering have dramatically reduced the value of rooftop solar exported to the grid, but rooftop systems can still help homeowners lower their utility bills by reducing how much electricity they buy from the grid — for now. If significant fixed monthly charges are adopted, however, that remaining value would be eroded; a homeowner who reduced grid electricity usage would have little effect in reducing their bills.

At the same time, AB 205’s inclusion of a July 2024 deadline for creating income-based fixed rates has forced the CPUC to prioritize that policy work ahead of its broader efforts to create more flexible and time-varying rates. The fixed-rate issue is being handled as part of the CPUC’s “demand flexibility rulemaking,” indicating the intentions it set for the proceeding before AB 205 changed its priorities.

“Fixed rates kind of got shoehorned into this proceeding,” Monahan of Sierra Club said. “But the primary focus of this proceeding is rates that change throughout the day.”

In his SEIA testimony, Beach emphasized that fixed charges “by definition do nothing to encourage the stated goal of this rulemaking — encouraging customers to be flexible in when they impose demands on the electric system.”

Proponents of reducing the value of rooftop solar have highlighted the problem of solar-equipped customers lowering their utility payments, potentially at the expense of customers without solar who will need to pay a higher share of overall utility costs to make up the difference. But this rooftop solar “cost shift” pales in comparison to the rising costs of utilities hardening their grids, burying power lines, building new transmission infrastructure and other fixed costs.

That means income-based fixed charges, time-varying rates and any other rate-structure policy are just “part of a spectrum of solutions to rate issues in California, and preparing the grid to rely primarily on renewable energy,” said Campbell of the Public Advocates Office. “We want to move people off of using energy during peak demand, and transition to energy use when solar is plentiful at the middle of the day.”

But amid the debate over rate design, we’ve lost sight of the much bigger challenge of how to bring down utility costs overall, Campbell said. “We’ve been taking everything that utilities have collected as a given,” he said. “I’ve told commissioners, you can’t rate-design your way out of high costs.” Solving the problem of soaring electric bills will require broader efforts to control the costs of operating California’s utilities in an era of climate change and decarbonization — a vital and highly complicated challenge that can’t be done by fiddling with rate structures.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Income-based electric bills: The newest utility fight in California on May 14, 2023.